"Knowledge and timber shouldn’t be much used till they are seasoned." — Oliver Wendell Holmes (1858)

One of my favorite things on Instagram is following along with planemakers as they craft new versions of these traditional tools. The well-known makers are definitely worth checking out, from Matt Bickford, Dan Schwank/Red Rose Reproductions, Jon Joffe, Jim White/Crown Plane, and Ryan Thompson, to Martin Harris, Simon Grace, Ben Bentley/Bentley Planes, Stavros Gakos, and Scott Smeek/Smeek Woodworks. But I also want to highlight some lesser-known planemakers, from smaller commercial makers to people making beautiful or interesting one-off projects. In a few months we'll look at a bunch more.

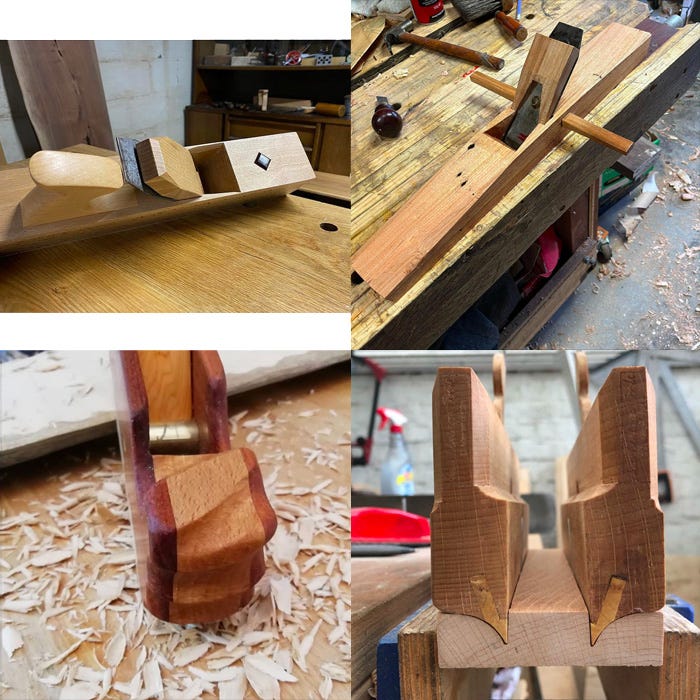

Top left: Elden McDonald. Top right: Richard Arnold (who’s also a preeminent scholar of 18th century English planemaking). Bottom: Joseph Thomas/Glenmere Hand Tools.

Top: Almira Planes (If you know my affinity for closed tote smoothers, you'll know how in love I am with Almira’s planes.) Bottom left: Mac Austin. Bottom right: Martha Downs.

Top left: Save The Electrons. Top right: bernardwoodwork. Bottom left: Mitch Peacock. Bottom right: NewVintageTools.

If you’re interested in making your own plane, there are a number of great books on the subject, including How to Make Wooden Planes by David Perch and Leonard Lee (ABE Books), John Whelan’s Making Traditional Wooden Planes (ABE Books), and Making and Mastering Wood Planes by David Finck (ABE Books), which is very good but unfortunately insanely expensive.

Last year I bought a beat up Francis Nicholson plane. Nicholson, if you're not familiar with him, is the first known commercial planemaker in America. He lived in Wrentham, in southern Massachusetts, and was active from the 1720s until his death in 1753. While his imprint is always a desirable find, it was actually the combination of both the maker's and owner's marks that got me excited. Alongside “F NICHOLSON LIVING IN WRENTHAM” is a distinctive "B MAN".

The B MAN mark has also been found on a Nicholson plow plane, as well as a plow made by Nicholson's son, John, and on a plane made by Jonathan Ballou (active 1751-1769 in nearby Providence, Rhode Island). Researcher Mike Humphrey thinks the Ballou plane may be a mismatched but functional mate of the Nicholson tongue plane I bought.

Richard DeAvila, one of the foremost wooden plane researchers and writers of his day, was the first to try and track down B MAN's identity — which isn’t easy. Man was a very common name in Wrentham. Samuel Man (1647-1719, sometimes spelled Mann) moved to the area in the 1660s to work as a minister. He had 11 children, nearly all of whom settled in Wrentham and nearby towns. As DeAvila discovered, the Nicholson and Man families were related by marriage: Samuel Man (1705-1740) married Francis's daughter Mehitable. Of all the Man relatives with the first initial B (see notes below), there are two that stand out: Samuel's brother Beriah (1708-1750), who DeAvila identified as a tanner and guessed may be B MAN. That's possible. But Samuel and Beriah had another brother named Benjamin, born in Wrentham in 1720. I don't know how long he lived there, but a carpenter named Benjamin Man married Wrentham-born Lydia Emily Harding in Providence in 1751 — coincidentally the same year Ballou began making planes in that city.1

Aside from his marriage, the first reference to Benjamin Man in Providence that I've found is the 1762 records of the Providence General Assembly where he was appointed a director of a lottery to pay for road improvements. In the ensuing years there are references to Benjamin Man being reimbursed for work including, "repairing the Windows of the Gaol," "finishing the Court-House," and "repairing the Gaol."2

The Providence Preservation Society has a record of Benjamin Man, "housewright," buying and then selling a house in 1768 on South Main St., "the same House and Lot I bought of my father-in-law Thomas Harding." The Society also has record of Benjamin Man, "house carpenter," selling a lot on Planet St. for "90 Spanish Milled Silver Dollars" in 1782. Benjamin Man submitted a bill for 10s-6 for glazing windows in a school house in November 1787. There's also a record of a Benjamin Mann/Man, "chandler," selling property in 1774. That may be another Benjamin, but considering the financial crisis of the late 60s/early 70s he may have branched out. There's only one Benjamin Man in Providence and Rhode Island in the 1774 general census, the 1777 military census, and the 1790 U.S. census. He died in 1794 and was buried in Cranston (on the border of Providence) next to Lydia, who died 10 years earlier. They had no children.3

So have I solved the mystery of B MAN? Nope, not even close. All I’ve shown is that a Benjamin Man with strong ties to Wrentham lived and worked as a carpenter in Providence during the right time period. Chronicling the early history of American planemaking often involves guesswork and conjecture, but even then the overlap between Benjamin and B MAN seems to be coincidental. One of the things I find most puzzling is why we've found four planes with this mark. Emil and Martyl Pollak estimate that a single 18th century planemaker could produce around 1,000 planes a year on their own.4 Assuming he worked up until his death, that would put Francis Nicholson's output conservatively at 25,000 planes. (He probably made many more, considering that he worked with his slave Caesar Chelor, who would go on to become another major 18th century planemaker.) Only about 210 Francis Nicholson planes have survived. How is it possible that we've found so many planes from a single carpenter who would have owned several dozen planes at most?

There's speculation that B MAN was a journeyman who worked for other planemakers and added his mark to the tools they made together.5 I wonder if in fact he was retailing planes and added his mark like hardware store dealers did in the 1800s. There's zero corroboration for this theory; no colonial planemaker did that as far as I know. But either theory would explain one confusing detail: the B MAN mark on the two separate plows. It would be strange for a single carpenter or jointer to own two expensive tools that did the same thing. Is it more likely B MAN was involved in the production or selling of planes than just a mere owner? Unfortunately that's where my sleuthing stops. I'm on the West Coast and I can't do any in-person research in Providence. But I hope I've added another chapter to this mystery.

— Abraham

was the first: Richard DeAvila. "Concerning the Stamp of B. Man and his Relationship to the Nicholsons." Plane Talk, vol. 8, no. 3, 1983. Samuel Man: George S. Mann. "Genealogy of the Descendants of Richard Man of Scituate, Mass." David Clapp & Son. 1884. related by marriage: Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1633-1850 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/519539:7853. born in Wrentham: New England Historic Genealogical Society. Massachusetts, U.S., Town Birth Records, 1620-1850 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 1999. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/39728:4094. when he married: Ancestry.com. Rhode Island, U.S., Vital Extracts, 1636-1899 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/6059411:3897. see notes: I eliminated Beriah, 1687-1734 (female), and Bezaleel, 1725-1796 (born in Wrentham, worked as a doctor for 50 years in Attleboro). Beriah, 1749/50-? (possibly born in Wrentham, unknown gender) and Benjamin, 1755-1835 (born in Walpole) are possible candidates but they wouldn't have been adults until well after the Nicholsons and Ballou were active. Beriah, 1746-1750, and Bathsheba, 1736-1736, died as children. (The Benjamin Man who worked as a doctor in Foxborough that DeAvila thought was a possibility wasn't born until 1814.)

where he was appointed: The records of the Providence General Assembly from 1769-1772 (https://archive.org/details/actsresolvesatge06rhod) and 1773-1775 (https://archive.org/details/actsresolvesatge07rhod) have numerous references to Benjamin Man. He was very civically active. He was a deputy to the General Assembly multiple times and served on several committees, including one "to prepare a Bill to prohibit the Importation of Slaves into this Colony" in September 1770.

buying and then selling: Mary A. Gowdy. "Records of #66 South Main Street...Brick." Mary A. Gowdey Library of House Histories, Providence Preservation Society, May 1967. https://gowdey.ppsri.org/gowdey/South%20Main%20St./66%20South%20Main%20St.pdf. selling a lot: Mary A. Gowdy. "Records of 328 Planet Street." Mary A. Gowdey Library of House Histories, Providence Preservation Society, Aug. 1972. https://gowdey.ppsri.org/gowdey/Planet%20St/28%20Planet%20St.pdf. submitted a bill: Myron O. Stachiw. The Old Brick School House. Providence Preservation Society, March 2014. https://ppsri.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/OBSH-HSR-Final-Report-PDF-NEW.pdf. chandler: Mary A. Gowdy. "Records of #326 Benefit Street....wood." Mary A. Gowdey Library of House Histories, Providence Preservation Society, Dec. 1964. https://gowdey.ppsri.org/gowdey/Benefit%20Street/326%20Benefit%20St.pdf. census: Colonial and US census data obtained via https://www.ancestry.com/search/categories/freeindexacom.

Emil and Martyl Pollak. A Guide to the Makers of American Wooden Planes. 4th ed. Astragal Press, 2001.

Elliot M. Sayward. "Notes & Queries." Plane Talk, vol. 7, no. 2, 1982.

Hi Abraham, Great detective work...there is of course an entire branch of historical work that focuses not on the great events, but rather on the small everyday activities of education, trade, healthcare, holidays etc. I think they call it social history, so you have pretty much initiated the social history of the wooden hand plane in this post! What caught my eye were the mention of the slave artisan, and the Bill for banning import of slaves. Thanks for mentioning the reality of the trade. We in the UK are (mostly) in massive denial or ignorance of how embedded slavery or the financial benefits of slavery were in every institution of the nation. That is changing slowly, as many institutions are not yet prepared to face up to the past. For anyone who is interested, there is a massive database held by University College London researchers where you can look up individual slave owners and traders https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/details/ and in t includes much data on their activities overseas. Given that much of the UK trade was contemporaneous with the activity in the Americas, maybe it will be a useful resource for researchers trying to better understand what was happening acriss the water. Keep them coming.